YASUHARU MATSUMOTO.

certified Nihon Cha instructor, co-founder Global Japanese Tea Association, vice-president of Obubu Tea Farms, Ikedoki Tea project. KYOTO.

green tea was having an international boom.

The world of Japanese tea is an example of challenges we have been witnessing in agriculture over the past couple of decades and perhaps an example of resilience in our sector.

Domestic consumption of Japanese tea represents the 93.75% of total sales.

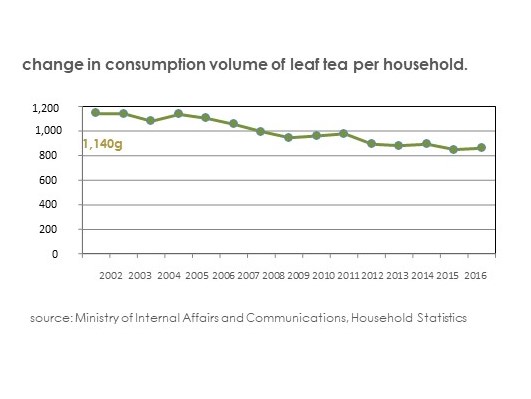

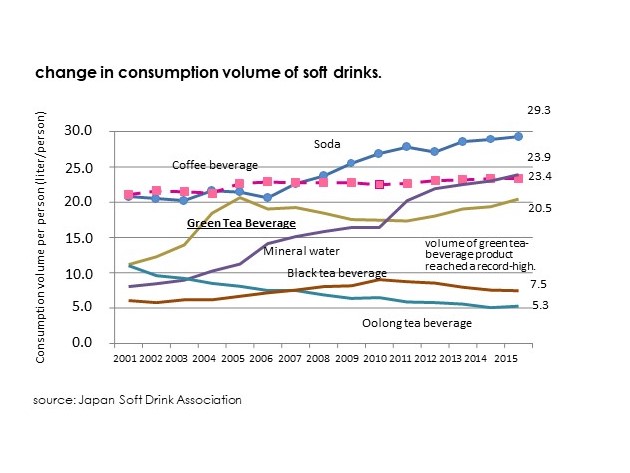

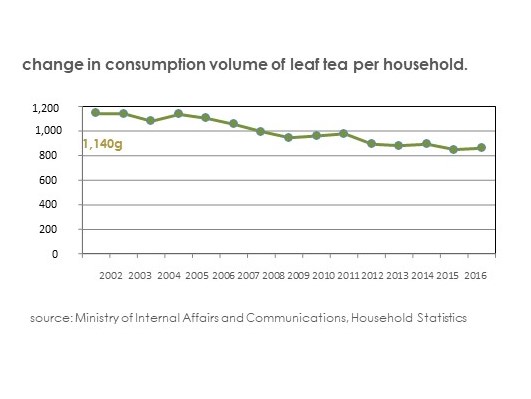

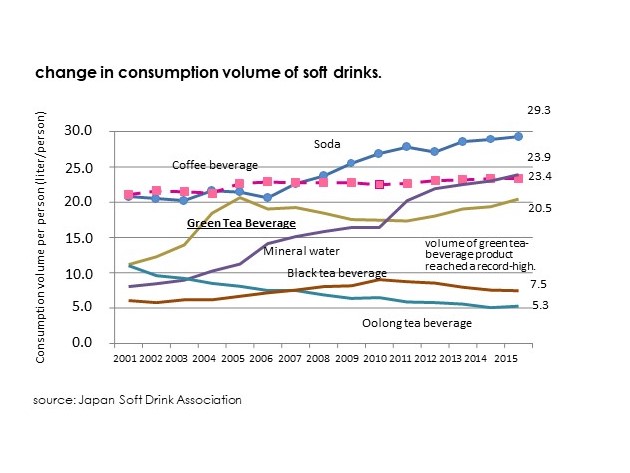

It has steadily declined over the last 15 yeas by approximately 30%; production and market prices have decreased accordingly. The current pandemic due to Covid-19 is expected to worsen the existing declining trend.

In 2020, from April 1st to the end of May Japan’s Government issued a National State of Emergency in response to the coronavirus – coinciding with the new tea season. It was a decision for which we had no control.

As a result, in each tea-producing region, the market price of the ‘first tea’ (new spring tea) has fallen below half it’s average price, the whole of tea stocks were sold. Such events, in turn, influenced the production of the second tea (summer new tea) and the third tea (autumn new tea), to a point where many producers renounced to harvesting them. Tea became one of the most significantly affected industries within the agricultural sector.

True, the decline of our industry has been in the making for long time, yet this year’s situation has been unprecedented. It has been an acceleration towards a further decline, particularly when taking into consideration other cumulative events and issues faced by the industry – as the aging of the agricultural population, and difficulties related to manpower and knowledge transfer. In Japan, the average age of agricultural worker is over 60 years old, and the number of workers is decreasing.

These cumulative effects will likely cause another major revolution in the Japanese tea industry.

Shizuoka Prefecture – for more than 100 years- the largest producer of tea in Japan – since the beginning of statistics – will lose it’s number one position in Japan to the Kagoshima Prefecture, currently the second largest producing region. An event that no one in the tea community has ever experienced; it is no exaggeration to say that it is comparable to a NATURAL DISASTER.

The historical peak of Japanese tea exports was in 1917, more than 100 years ago, when a record volume of 30,000 tons was exported. Back then, Japan was still a developing country and tea was the second most important export item after silk.

In 2019, tea exports amounted to only 5,000 tons so it is fair to say that there is still room for growth; it is thought widespread that exportation is the only trump card to overcome this predicament this is believed by production sites and in our communities at large.

Today, Japanese tea is recognized by tea lovers all around the world, for example, for a high-class green tea such as matcha, is also being used as a flavor in matcha ice cream. Research results have shown that green tea is effective as antioxidant also against viruses such as COVID-19 the consumption has increased over the past year.

For this, exports of green and other types of Japanese tea are expected to increase despite the corona situation, and we are hopeful for 2020 results.

In a way, the reader of this article can be the ‘savior’ of Japanese tea industry as the tea-producing regions resilience and survival is rooted in the possibility our teas becoming more and more popular worldwide to be used as a healthy and anti-aging drinks indispensable in the new normal era.

Let’s drink Japanese tea and survive together in this unpredictable era.